Walk into a HYROX event and you will notice something straight away. A surprising number of athletes have a nasal strip taped across their nose. It has become part of the look of the sport. A small signal that the athlete is serious about performance and has done their research. They warm up with it on and move into the start pen with confidence. Everything looks in place. Shoes ready. Mind ready. Tape ready. Then the race begins and within a few strides the mouth opens and the breathing switches straight into heavy mouth breathing. The nasal strip stays in place, but the nasal breathing does not. It is an interesting moment because the strip is still doing its job but the breathing system underneath it is not.

This pattern plays out again and again. Athletes use nasal strips with the hope that they will improve performance, but the strip is only an accessory. It helps a little if the breathing system is already trained. It does almost nothing if the athlete has never worked on breathing frequency, carbon dioxide tolerance or mechanics. This is why there is confusion around whether nasal strips help performance. They do help in certain conditions. They do not solve the underlying patterns that most athletes carry into training and racing.

HYROX gives us a useful lens because it exposes the breathing habits that are common across endurance sports. Many athletes breathe too fast at rest. They over breathe before the race has even started. Their breathing sits high in the chest. They lose control of their breathing rhythm when the work intensifies. Recovery periods become moments of collapse rather than moments of regulation. They grip the race with everything they have, which usually means the breath is left to chance. Understanding nasal strips begins with understanding these patterns.

This article examines whether nasal strips improve performance in HYROX and endurance sport, and why they are often misunderstood.

Nasal strips can support airflow through the nose by reducing external nasal valve collapse, particularly at low to moderate intensities or during recovery. However, they do not train the breathing system and do not improve breathing mechanics, breathing frequency or carbon dioxide tolerance, which are the primary drivers of performance.

Using HYROX as a practical example, the article explores common breathing errors seen in athletes, including over-breathing at the start line, high chest breathing, poor control under load and ineffective use of recovery moments. It explains how carbon dioxide sensitivity, fast breathing and loss of pacing reduce oxygen delivery and accelerate fatigue.

The article reviews current research on nasal strips, highlighting that performance improvements are small and context-specific, and that most studies fail to account for breathing behaviour, nervous system regulation and decision making under pressure.

It then outlines what actually improves breathing in sport, including nasal breathing at low intensity, carbon dioxide tolerance training, breathing mechanics, respiratory muscle training and controlled breathing frequency. The role of nasal strips is positioned as supportive rather than corrective.

This insight is written for HYROX athletes, endurance athletes, coaches and practitioners who want a clearer, evidence-based understanding of breathing, performance and recovery.

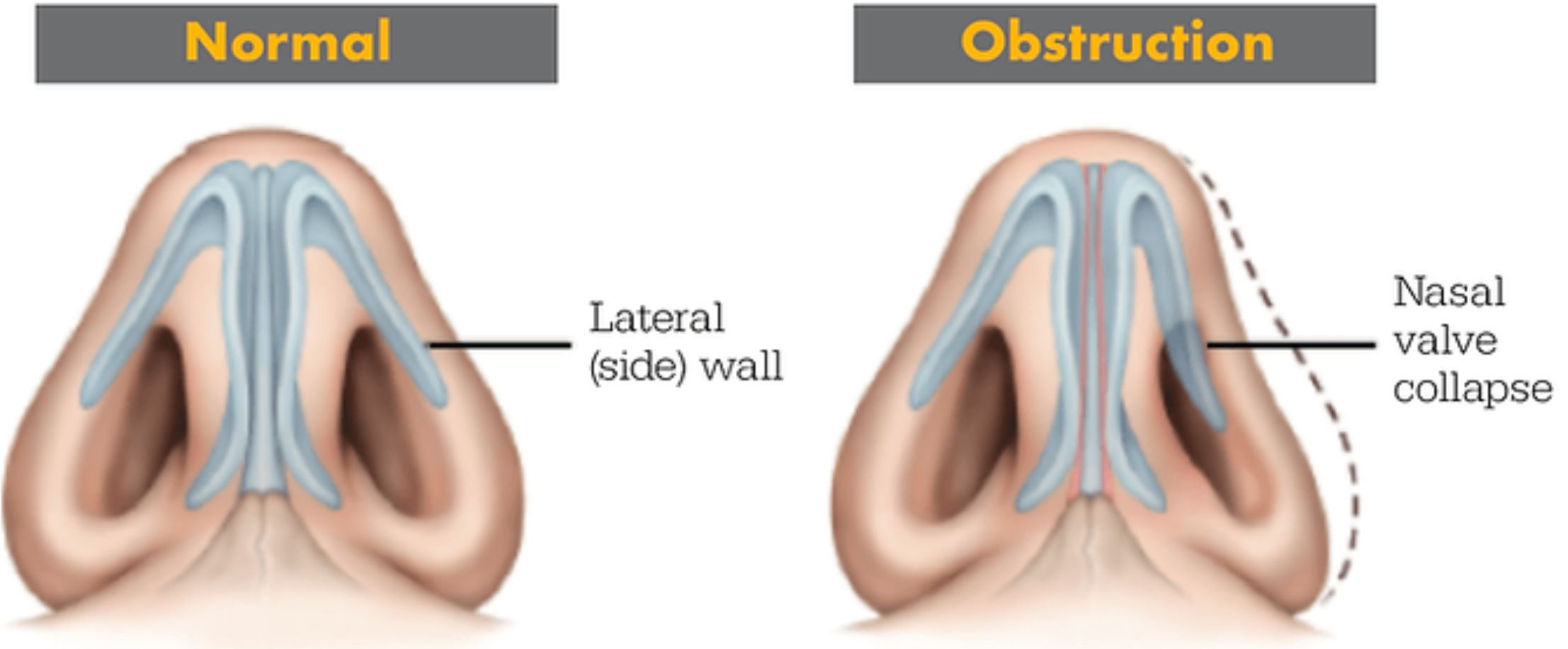

Nasal strips support the external nasal valve by lifting the skin at the lower part of the nose. This reduces the collapse of the valve and helps air move more easily through the nostrils. It is a simple mechanical effect. It does not influence rib movement or diaphragm range. It does not change breathing frequency. It does not alter carbon dioxide tolerance or how an athlete responds to stress.

The benefit is straightforward. If someone has mild nasal obstruction or if their nostrils collapse when airflow increases, the strip can make nasal breathing more comfortable. This can help during warm-ups, easy runs and steady conditioning. When intensity rises, the mouth will still need to take over. A strip cannot compensate for the deeper factors that shape how breathing behaves under pressure.

A key paper published in 2021 by Rezendeiani and Fieri examined the effects of external nasal dilators during sports activity. They found that strips can reduce perceived effort in some individuals and can be helpful for those who have structural nasal limitations. Performance improvements were small and tended to occur at moderate intensities.

Studies from 2022 to 2025 add more detail but follow the same pattern. Some show a small reduction in inspiratory resistance. Some show that nasal breathing becomes more comfortable when using a strip. Most do not show meaningful improvements in VO2 max, time to exhaustion or running economy. These studies are often done in controlled laboratory settings. They do not capture the complexity of HYROX where intensity, stress, movement patterns, decision making and fatigue interact constantly.

Most research isolates airflow as the main variable. Breathing is not only an airflow problem but a behavioural and physiological system that changes in relation to CO2 levels, functional breathing mechanics, nervous system state and regulation, pacing and psychological load. When these variables are not measured, the results only show a small part of the picture.

To understand why nasal strips often fall short, it helps to look at what actually happens in the body when an athlete works hard.

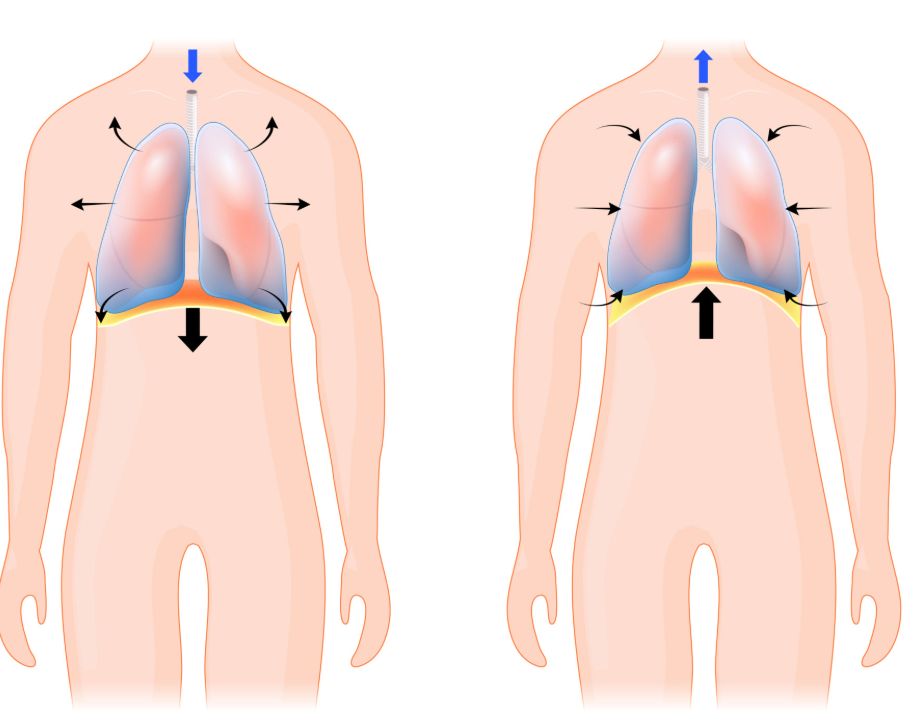

Breathing mechanics

The diaphragm needs to and does move down on inhalation and the ribs need to expand laterally. When breathing sits high in the chest and the shoulders lift on every inhale, breathing efficiency drops and the cost of breathing rises. Metabroreflex

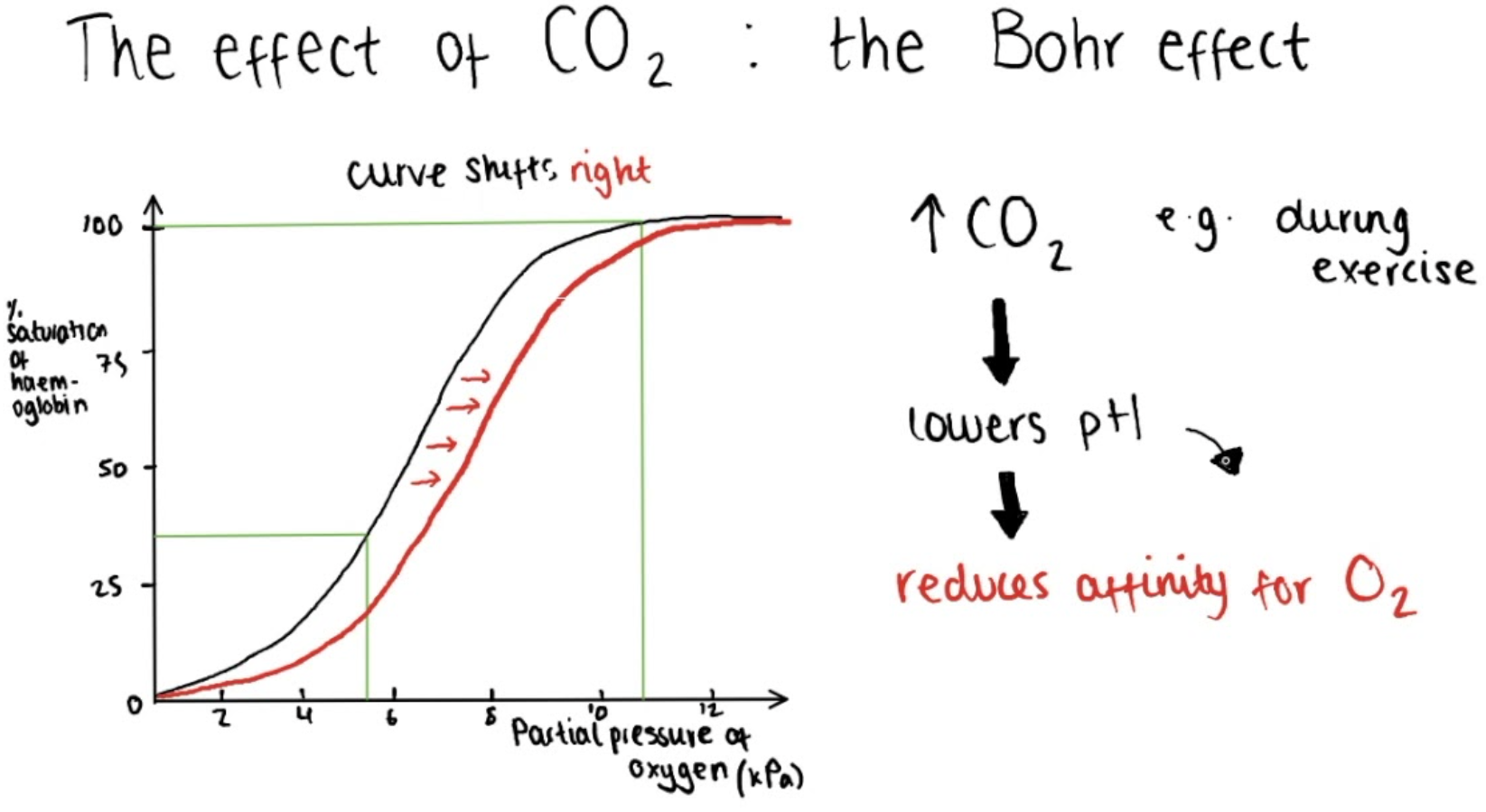

CO2 is the primary driver of breath. Athletes with low tolerance feel discomfort quickly and move straight into fast mouth breathing. A nasal strip does not change this.

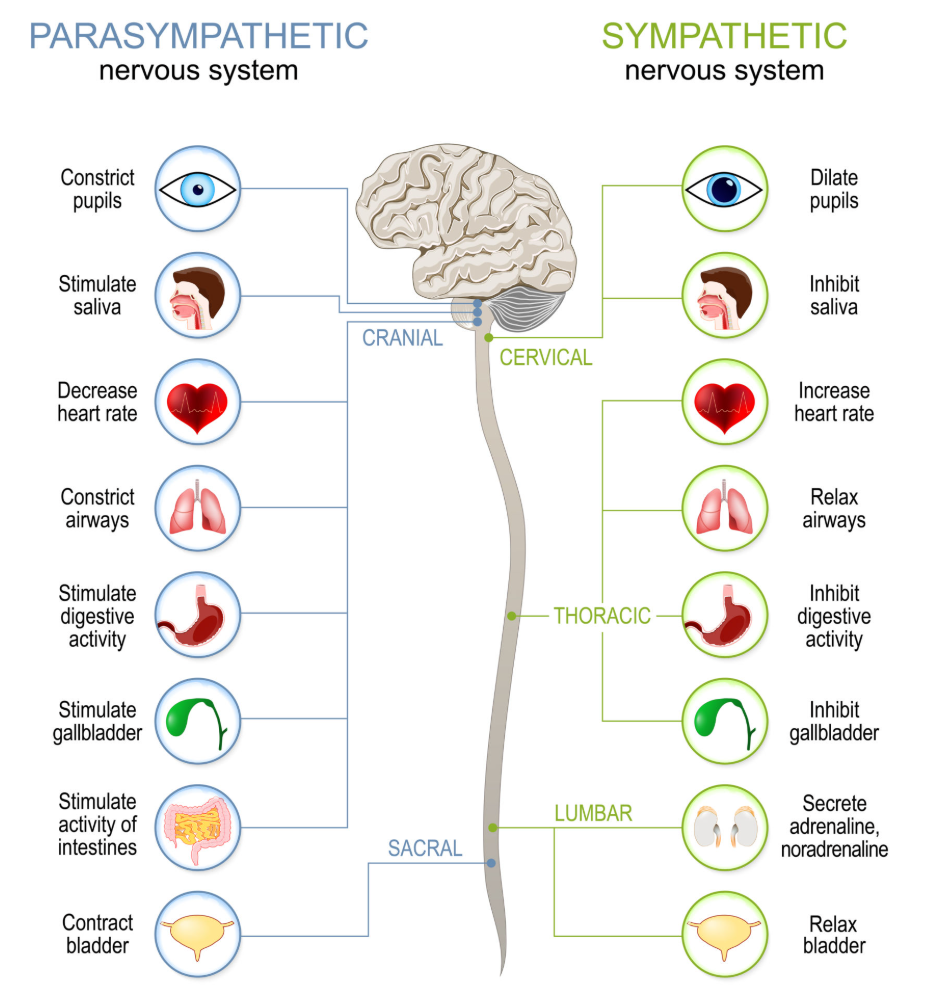

Fast breathing reduces CO2, which reduces oxygen release into the muscles through the Bohr effect. It also increases the metabolic cost of breathing.

The respiratory metaboreflex is a reflex that raises blood pressure and cardiac output during exercise by detecting metabolic by-products in active muscles. When muscles are working hard and oxygen delivery is insufficient, this reflex increases sympathetic nerve activity to constrict blood vessels in non-active muscles and increase blood flow to the active muscles. This ensures oxygen can be delivered to the muscles that need it most. When the respiratory muscles fatigue, blood flow is redirected from the limbs towards the respiratory muscles. In HYROX, this means sudden heaviness in the legs and arms.

Breathing reflects emotional state. When athletes lose control of their minds, they lose control of their breath. This affects movement, pacing and decision making.

None of this is measured in most nasal strip studies. This is why results often appear flat, even though athletes describe the race as anything but simple.

HYROX has a predictable breathing pattern for many athletes. Often increased breathing frequency at the start line and high chest breathing immediately into the runs. A loss of control during heavy work. Mouth breathing that becomes reactive rather than intentional and under some sort of deliberate control.

One of the most misunderstood areas in regard to recovery and regaining control of breathing is during the ROXZONE.

For experienced HYROX athletes, the ROXZONE isn't a recovery zone. It is part of the run. The distance through the ROXZONE is included in the overall race distance, and slowing down here costs time. Newer athletes often ease off as soon as they pass under the arch and drift toward the station. More experienced athletes keep moving with intent until they physically touch the equipment.

This matters because breathing regulation in HYROX doesn't happen simply because the ROXZONE exists. It happens because athletes create recovery within effort, not outside or in other words, recover in planned areas of the race.

In doubles races, recovery is built in. While one partner works, the other rests and recovers. This is where learned breathing tools can be applied deliberately. Not to return to calm nasal breathing, which is rarely realistic at race intensity, but to offload carbon dioxide in a controlled way so the system can reset before re-engaging. Using this and a system of 'gear' tested breathing to control heart rate is the key to HYROX success, in my opinion.

In solo races, recovery is self-imposed. Almost every athlete plans brief breaks on demanding stations such as the sled push or sled pull. Many also find moments during the ski erg or at the bottom of the burpee broad jumps where breathing can be brought back under control. These windows are short and uncomfortable, but they are where breathing decisions matter the most and should be thoughtfully imposed.

The common error is uncontrolled over breathing. This is usually driven by sensitivity to carbon dioxide. When CO₂ tolerance is low, the body responds by increasing breathing rate. As breathing becomes quicker and more upper chest driven, it shifts the nervous system into a more stressed, sympathetic state. Carbon dioxide is blown off rapidly because the athlete does not yet have control over it.

As CO₂ levels fall, blood pH becomes more alkaline. This matters because of what happens next. The oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve shifts, reducing the release of oxygen from haemoglobin into the working muscles. Blood flow is also affected. Despite breathing more, oxygen delivery actually becomes less efficient. Fatigue accelerates, the respiratory muscles demand more blood supply, decision making deteriorates, and pacing begins to fall apart.

This is where balance becomes important. Carbon dioxide is the primary driver to breathe, and during intense efforts, it will rise naturally. At certain points in a race, deliberately offloading CO₂ can restore control. But chronically over-breathing and remaining in a state of respiratory alkalosis for prolonged periods is not helpful and can impair cellular function. The aim is not to eliminate CO₂, but to regulate it, keeping blood pH close to its optimal range so oxygen delivery, blood flow, and performance can be sustained.

In simple terms, breathing more does not mean you are getting more oxygen, and learning to control your breath helps your body do more with less effort.

If, during these brief recovery moments, an athlete can fully exhale, reduce breathing frequency even slightly, and allow deeper breaths driven by the diaphragm with some lateral rib movement, that is a meaningful improvement. It is not about returning to nasal breathing and getting to use the nasal strips finally; it is about avoiding chaos and burout and regaining control.

HYROX also highlights the absence of breathing gears in athletes. Many athletes jump straight from light breathing to uncontrolled heavy breathing. They never build transitional patterns that help them move between intensities. These errors are common but are also trainable. This is where the warm up of the respiratory centre, respiratory muscles and ribcage are essential. Note: You don't have functional movement without functional breathing.

Breathing improves when the system underneath it is trained. A nasal strip cannot create these changes. It can only support airflow. The bigger changes/adaptations come from repeated practice and an understanding of how breathing, physiology and performance work together. HYROX gives us a clear look at this because the races always expose the areas where athletes tend to lose control and often fast. That's just the name of the game and so awareness and understanding of breathing limitations are essential. These are the foundations that make the real difference.

Nasal breathing at easy and steady intensities lays the groundwork for everything that follows. It helps athletes stabilise their breathing and manage the early signs of discomfort before intensity rises. The natural resistance created by breathing through the nose engages the diaphragm and encourages a deeper breath that reaches the lower lungs rather than sitting high in the chest.

Air that enters through the nose is filtered, warmed and humidified, which supports respiratory health and reduces irritation to the airways. Breathing through the nose also introduces nasal nitric oxide, a natural vasodilator that supports blood flow and oxygen delivery at the alveoli, where gas exchange takes place. When athletes mouth breathe at all intensities, these advantages are lost.

This is where using the nose whenever possible really matters, and where nasal strips can help by keeping the nasal airway open and comfortable. The higher an athlete’s carbon dioxide tolerance, the easier it becomes to return to nasal inhale and mouth exhale breathing during recovery. Anyone who has raced hard with a dry mouth and a foggy head knows how valuable that moment of control can feel.

CO2 tolerance shapes how an athlete feels under load. When tolerance is low, the body reacts quickly by increasing breathing rate and creating discomfort long before it is necessary. Improving CO2 tolerance helps the body settle into rising CO2 with less urgency. It supports better pacing and a calmer internal state when the work becomes harder.This begins before the race even starts. Many athletes stand on the start line with their mouths open, breathing quickly and washing out carbon dioxide. This creates an internal state that is not prepared for the metabolic load that arrives as soon as the race begins. CO2 rises fast, the body is surprised by it and the athlete feels breathless long before they should.

A better approach is to introduce a manageable rise in CO2 before the race starts. This prepares the respiratory centres in the brain for what is coming and allows the athlete to meet the first minutes of intensity with more stability. This can be done through light breath holding, short controlled breath reductions or work on the isocapnic device. It activates the diaphragm, increases awareness of the breath and helps the body reach its second wind at the start line rather than several minutes into the race.

HYROX demands constant CO2 handling because the intensity rarely drops. The athletes who train CO2 tolerance, and who arrive at the start line with CO2 already in the system, tend to feel steadier, more focused and more in control of their effort.

Mechanics shape the structure of the breath. The diaphragm needs to move downwards and the ribs need to expand laterally. When athletes lift their shoulders and breathe high into the chest, breathing becomes inefficient and expensive. Mechanical training teaches athletes to stabilise their breath under pressure. This includes positional work, mobility, awareness and consistent practice. Strong mechanics support every part of performance.

The respiratory muscles fatigue like any other muscle. When they do, the metaboreflex redirects blood away from the limbs. In HYROX this means a sudden drop in strength and power. Strengthening the breathing muscles reduces this effect and improves control at high intensities. I use the Isocapnic device with many athletes because it provides structured resistance training for the respiratory muscles. It is one of the most overlooked areas in performance. If you want more information on how this fits into your training, feel free to ask.

Breathing frequency shapes oxygen delivery and nervous system state. Many athletes begin a race already breathing too quickly. Once the breath becomes fast and shallow, CO2 is washed out and oxygen is delivered less effectively due to the Bohr effect. Slowing and stabilising the breath is a skill that needs practice at rest and in lower intensity work. When athletes can regulate their breathing rate, they recover more effectively and feel more composed under pressure.

For experienced HYROX athletes, the ROXZONE is not a recovery zone. Recovery is created within effort, either while a doubles partner is working or during brief, self-imposed pauses on demanding stations, where controlling the breath and offloading excess carbon dioxide prevents fatigue from compounding.

Matching breathing to running cadence or movement rhythm helps reduce stress on the system and keep the breath under control. It creates a predictable pattern that the body can follow. It reduces cognitive load and helps the athlete maintain pacing. When cadence stabilises, breathing becomes more rhythmic and easier to sustain whilst offsetting excess CO2.

These foundations make the difference. Nasal strips can be used alongside them but they cannot replace breathing training. When athletes build these skills, breathing becomes reliable and predictable. When they do not, breathing becomes reactive and unpredictable no matter what accessory they wear.

They can reduce external nasal valve collapse.

They can make nasal breathing feel more manageable -at low and moderate intensities.

They can support nasal breathing during warm ups and steady conditioning.

They can help beginner athletes stay nasal during recovery windows in the ROXZONE or help competitive athletes regain breathing control during small recovery breaks.

They can improve comfort for athletes with mild structural nasal restriction.

They can make sleep time nasal breathing easier.

They can help maintain airflow when breathing rate rises slightly and have a low CO2 tolerance.

They can support athletes who struggle with mild nasal obstruction or collapse under load.

They do not improve carbon dioxide tolerance.

They do not slow breathing.

They do not support diaphragm function.

They do not influence the metaboreflex.

They do not correct high chest breathing.

They do not train breathing mechanics.

They do not settle anxiety or improve pacing.

They do not improve decision making or create calm under pressure.

HYROX has created a situation where nasal strips are everywhere, on amateurs and pros alike. They are worn because everyone else is wearing them, not because people understand what they are for. If you are racing flat out, mouth open, breathing fast and shallow from the first run, the strip is not contributing anything meaningful. Without breathing training behind it, it is just something stuck on your face. The real gains come from learning how to control breathing under load, how to manage CO2, how to pace the breath when fatigue builds, and how to recover when it matters. Until that work is done, the strip is irrelevant.

From a personal point of view, I need to be clear about something. Nasal strips and sleep tape have been genuinely important for me. Without them, I would not be doing this work. I broke my nose badly as a teenager and have lived with a deviated septum ever since. For years it affected my sleep, my energy, my health, and my performance in ways I did not fully understand at the time. Around 7 to 10 years ago I discovered sleep tape and nasal strips, and they changed how I slept, how I trained, and how I felt day to day. I do not exercise without them. I do not sleep without them. They allow me to breathe through my nose at night and recover properly, and that has had a knock on effect on every part of my life.

So this is not an argument against nasal strips. It is an argument against thinking they are the answer on their own. They are a tool, not the work. If you take the time to understand your breathing, train it properly, improve your mechanics, your CO2 tolerance, your pacing and your recovery, the strip can support that. If you do not, it will not. HYROX performance improves when the foundations are in place, and the same is true for health, energy and resilience outside of sport. Breathing trains and influences all of it. If you want better performance and a more stable and healthy body and mind, the question is not whether you should wear a strip. It is whether you are prepared to actually train your breathing to reap the benefits.

If you want to improve your breathing in HYROX, running, cycling or any endurance sport, we can help you build a functional breathing system that supports your performance. We work with individuals, HYROX gyms, running clubs, coaching teams and workplaces that want to understand breathing at a deeper level. This includes managing stress, improving recovery and building a healthier breathing system that holds under pressure.

If you want to explore this further, you are welcome to reach out or click on the blue button to book a free consultation.

Thanks!

Thomas

They can improve airflow through the nostrils if an athlete experiences external nasal valve collapse or mild nasal obstruction. This can make breathing feel easier at low to moderate intensities and during recovery moments. They do not improve performance on their own because they do not change breathing mechanics, breathing frequency or carbon dioxide tolerance, which are the factors that actually drive performance in HYROX.

They can be useful for some athletes, particularly during warm-ups and brief recovery moments, but most of the race will still require mouth breathing due to the intensity. A nasal strip can support airflow but it will not prevent breathlessness or fatigue if breathing is untrained.

Because most athletes have never trained their breathing. As soon as intensity rises, the body defaults to mouth breathing to clear carbon dioxide quickly. Without breathing training, the strip remains on the nose but the breathing pattern underneath it is unchanged.

No. High-intensity exercise requires rapid carbon dioxide clearance that nasal breathing alone cannot provide. Trying to force nasal breathing at maximal effort usually increases distress rather than improving performance. Control comes from training, not forcing.

No. Carbon dioxide tolerance is a physiological adaptation that is trained through specific breathing practices, exposure to controlled discomfort and consistency over time. A nasal strip does not influence this process.

Yes. Nasal breathing during low-intensity training builds the foundation for breathing control, diaphragm engagement and carbon dioxide tolerance. This makes it easier to regulate breathing when intensity increases, even if mouth breathing is required during the race.

They can help some athletes during brief recovery moments if nasal airflow is limited by collapse or obstruction. Recovery is still primarily driven by breathing frequency, mechanics and nervous system regulation, not the strip itself.

Current evidence does not show meaningful improvements in VO2 max, time to exhaustion or running economy from nasal strips alone. Any perceived benefit is usually related to comfort rather than physiological change.

Yes. Many people find nasal strips helpful for maintaining nasal breathing during sleep, especially when combined with sleep tape. Better sleep breathing can support recovery, energy levels and overall health.

No. It is an accessory. Without breathing training, it does not change how you breathe under stress, fatigue or pressure.

Holmgren, A. and Finnegan, S. 2024. Breathing mechanics and performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning for Sport.

Keller, M. and Ray, A. 2025. The metaboreflex and skeletal muscle blood flow during high intensity mixed modality exercise. Applied Physiology Report.

Kimura, S. and Obata, T. 2025. Nasal airflow resistance and recovery quality in hybrid competition athletes. Journal of Endurance Science.

Langer, N., Rittner, L. and Holm, P. 2023. Effects of nasal valve support on running economy in recreational athletes. European Journal of Applied Physiology.

Naito, T., Onishi, H. and Kuriyama, S. 2022. Influence of external nasal dilators on perceived exertion during moderate exercise. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance.

Perez, J. and Coleman, K. 2024. Carbon dioxide tolerance and breathing frequency in endurance performance. Sports Medicine Review.

Rezendeiani, R. and Fieri, C. 2021. Does the external nasal dilator strip help in sports activity. A systematic review and meta analysis. Journal of Physical Education and Sport.